So I got it!

And we played it!

And here is my review, both of Hillfolk and Blood on the Snow, the companion book that further expands the Dramasystem that Hillfolk establishes. The Dramasystem is published by Pelgrane Press and primarily written by Robin D. Laws with many guest authors for the settings (see below).

Design Notes:

There are two nicely bound books, both around 200 pages each with full color full page illustrations. They are on par with the production quality of the old 3.5 D&D books (the last physical RPG books I bought...).

Most of the art is pitch perfect, while some of the other art falls utterly flat:

The text is presented in the standard two column format that has a sometimes confusing mix of hint boxes that consolidate rules (in a way the text never does), dramatic quotes ("You again!" -> "I told you I'd be back, when you least expected it.") (that I suppose is the author's way of showing how he thinks the game should sound like?), and the main text.

I have been consistently frustrated with the organization of the book, and it seems that others have been as well because there are several rule consolidating pdfs that fit on a single page as reference to use during play. This is a great resource, but its frustrating that the texts themselves don't fulfill this purpose.

One of the highlights of both books is the "Additional Settings" sections that take up the last half of both books. They are written by guest authors and illustrated by guest illustrators so there is a tonal shift in the writing and the art midway through the book, but many of the ideas are gold.My players and I were very intrigued by the additional settings, so to give a glimps at what the published texts claim to be able to simulate play in, here are some examples:

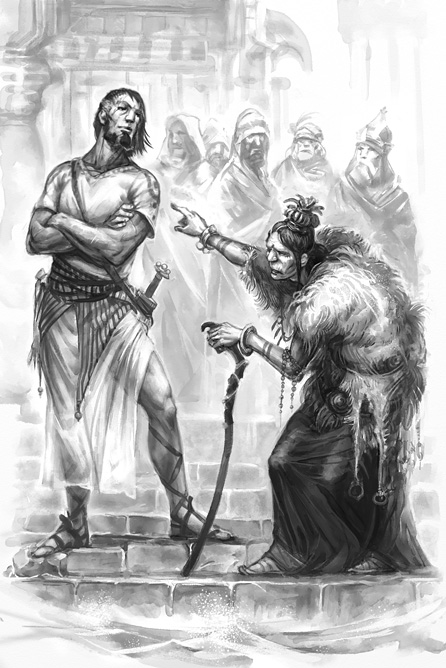

Most of the art is pitch perfect, while some of the other art falls utterly flat:

|

| Good art (Hillfolk) |

|

| Off color art (Blood on the Snow) |

The text is presented in the standard two column format that has a sometimes confusing mix of hint boxes that consolidate rules (in a way the text never does), dramatic quotes ("You again!" -> "I told you I'd be back, when you least expected it.") (that I suppose is the author's way of showing how he thinks the game should sound like?), and the main text.

I have been consistently frustrated with the organization of the book, and it seems that others have been as well because there are several rule consolidating pdfs that fit on a single page as reference to use during play. This is a great resource, but its frustrating that the texts themselves don't fulfill this purpose.

One of the highlights of both books is the "Additional Settings" sections that take up the last half of both books. They are written by guest authors and illustrated by guest illustrators so there is a tonal shift in the writing and the art midway through the book, but many of the ideas are gold.My players and I were very intrigued by the additional settings, so to give a glimps at what the published texts claim to be able to simulate play in, here are some examples:

- Support group for mad scientists

- Undercover CIA agents spying on Soviet Moscow

- Courtiers fighting over the realm of the Rabbit King (think Watership Down)

- An ant colony fighting the war on two fronts against a rival colony and a zombifying funagl pathogen

- Professional Wrestlers turned thugs for hire in 1980s Ohio

- Augustan intellectuals dukeing it out in 1700s London

- Hyper-capitalist robot drama in a post organic earth

- Orcs squabbling for the Chieftainship

- Ninjas

- A ship lost voyaging in Dreamspace, looking for reality

- Robodoctor medical drama

- Dolphin eco-quest

- Magicians secretly fighting in WWI

- Recently dead ghosts hang out together

- Teenaged battlemecha pilots from Japan and America are stationed at the same base

- And many more!

Basically if you can imagine a TV drama you can play that. The settings section also gives some good fodder if you want to run another game system with the setting concept.

System Outline:

Lets briefly break down some of the mechanics for the uninitiated masses. This is not a table top RPG in the sense that D&D or Pathfinder or Warhammer are, this is Role Playing. There are no dice, your character doesn't level up and hardly has statistics, gold and treasure don't matter, and most of the game is represented by "scenes" between players.

It is in short a story game.

Character Creation:

Characters are created as a group in the first session of play. Every one sits down together and decides on a setting (in my groups case the canon Hillfolk setting, Iron Age Middle East) and then take turns make declarations about their own character and their relationships with other characters. For example:

- Get named (Jaw Bone, Savy, Flint, etc)

- Their roles in their tribe are determined (chieftain, medicine woman, lead scout, etc)

- Relationships between characters are established (siblings, lovers, raid partners, etc)

- Desires are declared (I want respect!), with a strong emphasis on desiring more abstract emotional goals than concrete ones

- Dramatic poles are chosen (spirituality or carnality?) that show how the character wavers between their conflicting natures

- State something they want from any other character, the other character in turn tells them exactly why they can't have it ("I want your approval father!" -> "You will never have it because I loved your mother and I blame you for her death" etc)

- Choose their strengths and weaknesses by ranking the following "stats" (you get 2 strong, 3 middling, and 2 weak): Enduring, Fighting, Knowing, Making, Moving, Talking, Sneaking

Once this process is done you have a fully formed web of relationships that can be mined for dramatic narrative tensions. The youtube video I linked to above does a good job of walking you through this using the TV show Breaking Bad as an example of how these narrative tensions look in a story that we are familiar with. There are also cool relationship webs that look like this:

Pacing (Episode vs Scenes):

Each session, as most of us would call the thing where we sit down together for a few hours to play a game and then come back for another one next week, are instead called episodes. Each episode has a theme that is chosen first by the GM (game moderator) then by the a randomly chosen player at the end of the episode before. Themes are things like: Hunger, Change is Hard, What's In a Name?, Progress, etc. Themes should be brought up and built upon or highlighted through their absence. i.e. the chief isn't going hungry when everyone else is licking rocks which highlights the absence of Hunger.

Within an episode scenes are called. First by the episode caller, then by a randomly chosen precedence order that cycles back around once everyone has called a scene. A scene has: a cast of characters who are there (and even what they are doing, "Jaw Bone you are evesdropping, feel free to chime in when/if you see fit), a setting (down in the training yard, out by the freshwater spring, in my hut, around the central fire, etc), a time (especially if this is much later/earlier than the previous scene), and a "mode" (whether this is to be a dramatic scene or a procedural scene). Often the character calling is designated as the "petitioner", the person going into the scene with something they want on their mind. The caller doesn't even have to be in the scene and can designate anyone the petitioner.

Any one of the above attributes of a scene can can challenged by anyone at the table. Don't want your character in the scene? Just say so and the caller can allow or try and stop you from "ducking the scene". Or if the caller is amenable to the alteration it just happens, This is true for most of the game, there is a lot of negotiation and consulting with everyone for narrative elements.

Dramatic vs Procedural Scenes and the Relationship Economy:

Once the scene is called the cast begins to engage with it. This kind of just looks like talking if the scene is a dramatic one, think of a Game of Thrones scene where two or three characters are just being snide to each other and threatening and bargaining. Scenes should only take a few minutes, and once they start getting too long other characters can call "end scene!" to speed things up. At the end of the scene the petitioner says whether or not they feel like they got what they want from the scene. If they didn't get what they wanted they are given a "Drama Token", if they did get what they wanted they give a Drama Token to the one that conceded to them.

When players are in a procedural scene they tend to be in conflict with each other or some abstract opponent (a cliff face, a rival tribe, a herd of wild hores, etc) that they want to win dominance over. So if a character is challenging the chief for rulership they would have a procedural fight. This involves a deck of cards and drawing to match a target card. Its a little complex and I won't get into it here.

The Drama Tokens are a way to reward flexibility with narrative influence. If you allow your character to give a dramatic consession you can later spend that token for something that matters to them. They can be used to force scenes to happen the way they want, advantage in procedural resolution, and other boons.

When players are in a procedural scene they tend to be in conflict with each other or some abstract opponent (a cliff face, a rival tribe, a herd of wild hores, etc) that they want to win dominance over. So if a character is challenging the chief for rulership they would have a procedural fight. This involves a deck of cards and drawing to match a target card. Its a little complex and I won't get into it here.

The Drama Tokens are a way to reward flexibility with narrative influence. If you allow your character to give a dramatic consession you can later spend that token for something that matters to them. They can be used to force scenes to happen the way they want, advantage in procedural resolution, and other boons.

Play Test Report:

My group and I played 4 episodes in the stock standard Hillfolk setting. We had a cast of 6 players all playing a family closely related to the current chief of their tribe.

Character Creation:

This took a majority of the first session. We sat down and literally read out of the book step by step how to create characters and it actually worked surprisingly well. This is a central part of the game set up, as having a sufficiently complex web of desires and relationships is what drives the whole game and the system that is presented is a good way to create these relationships.

Play:

In all honesty, it was pretty fun! There is a sufficient amount of structure to provide snappy and interesting play, but plenty of room (mile and miles of room) for creative collaboritve improvisation.

The largest complaint my group had about the system was the procedural scene resolution. Its clunky and we had to re-read through the rules each time we had a procedural scene. I don't think we ever satisfactorily learned.

It was also difficult to play with more or fewer players at a session, you are really tied to the cast of characters that you begin play with and its very hard to incorporate new players into the webs of relationships. On the flip side of the same coin, if you don;t have the whole cast present much of the tenssion dissolves; I am sure I am not alone in having trouble getting the exact same group of people together weekly for several hours at a time and having play rely on that is a significant weakness.

The largest complaint my group had about the system was the procedural scene resolution. Its clunky and we had to re-read through the rules each time we had a procedural scene. I don't think we ever satisfactorily learned.

It was also difficult to play with more or fewer players at a session, you are really tied to the cast of characters that you begin play with and its very hard to incorporate new players into the webs of relationships. On the flip side of the same coin, if you don;t have the whole cast present much of the tenssion dissolves; I am sure I am not alone in having trouble getting the exact same group of people together weekly for several hours at a time and having play rely on that is a significant weakness.

In Summary: What You Should Steal

The real innovation of Dramasystem is the web of relationships, I want to use it everywhere. You could have a fast version of the character creation process when rolling up a new party for D&D. This sets up the adventure to be more than just a hack and slash rampage through a dungeon. Having everyone give predefined relationships with each other also meets one of my goals of having a community driven adventuring party. It would also be a useful system to define tensions at a larger scale by running through the process with the factions in a setting (the Bloobloods want the capitol city of the Annix Empire back as their holy city, but the Empire will never let them have it because they think the Bloobloods are a shattered and broken people...)

The dramatic scene system has use in carousing. The party gets back to town and tries to blow off some steam and maybe some tension boils over (Matild! How could you let Hiens get slashed by the orc assassin, you know he is my little brother! I swore to protect him!) This also fits in with the longer time skips I am using in my games to allow for community scale events. The dramatic scene is also a way better way to handle negotiation with NPCs, certainly much better then rolling against a diplomacy DC!

The procedural scenes, as written, are my least favorite part of the system and I would scrap them completely. D&D and other simulation style games are built to handle these kinds of conflicts and do it better than Dramasystem attempts to.

Rating: *** /*****, worth checking out (more so with Blood in the Snow), but maybe not worth buying the hard copy, especially if you can't stand story games

The dramatic scene system has use in carousing. The party gets back to town and tries to blow off some steam and maybe some tension boils over (Matild! How could you let Hiens get slashed by the orc assassin, you know he is my little brother! I swore to protect him!) This also fits in with the longer time skips I am using in my games to allow for community scale events. The dramatic scene is also a way better way to handle negotiation with NPCs, certainly much better then rolling against a diplomacy DC!

The procedural scenes, as written, are my least favorite part of the system and I would scrap them completely. D&D and other simulation style games are built to handle these kinds of conflicts and do it better than Dramasystem attempts to.

Rating: *** /*****, worth checking out (more so with Blood in the Snow), but maybe not worth buying the hard copy, especially if you can't stand story games

No comments:

Post a Comment